There is no reliable way to predict top performers in the stock market. Research shows this. We know that broad diversification helps reduce unnecessary risk associated with exposure to a single stock, sector, or country. However, millions of investors refuse to accept the evidence.

In 2017, The Wallstreet Journal published a 15-year study that found 92% of active stock pickers underperformed their benchmark. This is merely one of the countless studies that supports Nobel Laurette Eugene Fama, PhD, and his groundbreaking research about market efficiency first published in 1970.

Moreover, Nobel Laurette Bill Sharpe, PhD, once described the arithmetic of the market as a zero-sum game. This theory states that, at any given time, the market consists of the cumulative holdings of all investors, and that the aggregate market return is equal to the asset-weighted return of all market participants. Since the market return represents the average return of all investors, for each position that outperforms the market, there must be a position that underperforms the market by the same amount, such that, in aggregate, the excess return of all invested assets equals zero.

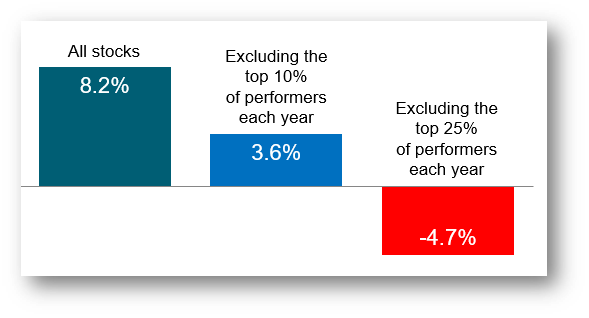

Compound average annual returns: 1994–2020

If you owned all stock over the 26-year period from 1994 to 2020, the return would have been 8.2%.[1] However, if you excluded just the top 10% of performers each year, you would have earned only 3.6% a year — that’s a decrease of 56%. If you excluded the top 25% of performers each year, you would have seen returns drop to -4.7%.

The probability of being able to predict good performance is miniscule. The best way to reduce risk is diversification.

Visualize a distribution curve. Long tails drive everything. For example, out of more than 21,000 venture capital financing from 2004 through 2014:

- 65% lost money

- 2.5% made a 10x to 20x return on investment

- 1% made more than a 20x return

- Just 0.5% (about 100 companies out of 21,000) earned a 50x or more return

Morgan Housel points out in his book, The Psychology of Money, that 40% of the U.S. stocks in the Russell 3000 Index have lost 70% of their value and never recovered. Effectively, all of the returns from the Russell 3000 have come from about 7% of component companies that outperformed by at least two standard deviations.

Again, being able to predict returns is like flipping a coin – the probability of continually, consistently making accurate predictions is impossible. Investors who diversify their portfolios are protecting wealth, and they’re a step closer to becoming financially unbreakable.

Warren Buffett’s Bet

Warren Buffett is generally respected as a savvy investor. He has said, “When trillions of dollars are managed by Wall Streeters charging high fees, it will usually be the managers who reap outsized profits, not the clients.”

Buffet’s position is more than mere words. In 2007, Buffett issued a challenge to the hedge fund industry, which in his view charged exorbitant fees that the funds’ performances couldn’t justify. Protégé Partners LLC accepted his challenge, and the two parties placed a million-dollar, 10-years-long bet.

Ted Seides was the co-founder of Protégé Partners. For the bet, he selected five fund of funds that were collectively invested in over 100 actively managed hedge funds. Conversely, Buffett selected Vanguard’s S&P 500 Index Fund (VFIAX). Beyond the economics of the bet itself, all 100 hedge funds as well as the fund-of-fund managers were economically incentivized to outperform the market — most hedge funds charge a 2% management fee and collect a 20% performance fee.

But in the end, the actively managed hedge funds got clobbered. (And keep in mind, the 10-year competition included the 2008 financial crisis.)

Over the 10-year bet, Vanguard’s S&P 500 Index Fund returned 125.8%, and the five fund-of-funds representing over 100 hedge funds returned 36.3%. In fact, not one of the five institutional hedge fund investment vehicles had managed to beat the S&P 500 index that the Vanguard fund tracked.

In his shareholder letter, Buffett said that the financial “elites” had wasted over $100 billion over the past decade by refusing to settle for low-cost index funds. He also pointed out that the harm was not limited to the wealthy: State pension plans have invested with hedge funds, and “the resulting shortfalls in their assets will for decades have to be made up by local taxpayers.”

Does this mean that a money manager can’t make predictions that prove economically favorable? No.

Does outperformance over one, three, or five years convey skill? The past 50 years of empirical evidence would suggest no.

Coin Flippers

Let us conclude with an excerpt from Warren Buffett’s 1984 article, “The Superinvestors of Graham-and Doddsville“:

“Before we begin this examination, I would like you to imagine a national coin-flipping contest. Let’s assume we get 225 million Americans up tomorrow morning and we ask them all to wager a dollar. They go out in the morning at sunrise, and they all call the flip of a coin. If they call correctly, they win a dollar from those who called wrong. Each day the losers drop out, and on the subsequent day the stakes build as all previous winnings are put on the line. After ten flips on ten mornings, there will be approximately 220,000 people in the United States who have correctly called ten flips in a row. They each will have won a little over $1,000.

Now this group will probably start getting a little puffed up about this, human nature being what it is. They may try to be modest, but at cocktail parties they will occasionally admit to attractive members of the opposite sex what their technique is, and what marvelous insights they bring to the field of flipping.

Assuming that the winners are getting the appropriate rewards from the losers, in another ten days we will have 215 people who have successfully called their coin flips 20 times in a row and who, by this exercise, each have turned one dollar into a little over $1 million. $225 million would have been lost, $225 million would have been won.

By then, this group will really lose their heads. They will probably write books on ‘How I turned a Dollar into a Million in Twenty Days Working Thirty Seconds a Morning.’ Worse yet, they’ll probably start jetting around the country attending seminars on efficient coin-flipping and tackling skeptical professors with, ‘If it can’t be done, why are there 215 of us?'”

Buffet’s point: Predicting a coin toss accurately has nothing to do with skill. And much like those coin flippers, hedge fund managers accurately predicting economic returns has nothing to do with skill. So why do some investors believe them?

Buffett summed it up this way in his 1996 Berkshire Hathaway Chairman’s Letter: “Most investors, both institutional and individual, will find that the best way to own common stocks is through an index fund that charges minimal fees. Those following this path are sure to beat the net results (after fees and expenses) delivered by the great majority of investment professionals.”

[1] “All stocks” includes all eligible stocks in all eligible Developed and Emerging Markets at their market cap weights. Eligible stocks are required to meet a minimum market capitalization requirement. REITs and investment companies are excluded. Compound average annual returns are computed as the compound returns of the value-weighted averages of the annual returns of the included securities. “Excluding the top 10%” and “Excluding the top 25%” are constructed similarly but exclude the respective percentages of stocks with the highest annual returns by security count each year. Individual security data are obtained from Bloomberg, London Share Price Database, and Centre for Research in Finance. The eligible countries are: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, Chile, China, Colombia, Czech Republic, Denmark, Egypt, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hong Kong, Hungary, India, Indonesia, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Republic of Korea, Malaysia, Mexico, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Peru, Philippines, Poland, Portugal, Russia, Singapore, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Taiwan, Thailand, Turkey, United Kingdom, and the United States. Diversification does not eliminate the risk of market loss. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

This blog is for informational purposes only. It should not be retransmitted in any form without the express written consent of Delap Wealth Advisory, LLC, an investment advisor registered with the United States Securities & Exchange Commission. The contents of this communication should not be construed as investment advice intended for any particular individual or group of individuals. All information, statements, comments, and opinions contained in this blog regarding the securities markets or other financial matters is obtained (or based upon information obtained) from sources which we believe to be reliable and accurate. However, we do not warrant or guarantee the timeliness, completeness, or accuracy of any information or opinions presented herein. Any historical price or value is as of the date indicated. Information is provided as of the date of this material only and is subject to change without notice.

Investing in securities involves the risk of loss, including the risk of loss of principal, which clients should be prepared to bear. No assurance is given that the investment objectives of any investment described in this communication will be achieved. PAST PERFORMANCE IS NOT INDICATIVE OF FUTURE RESULTS. The information contained in this blog is not intended as tax or legal advice, and Delap Wealth Advisory, LLC, does not provide any tax or legal advice to clients. You should consult with our firm or other independent financial, legal, and/or tax advisors before considering any investment or participation in any investment program.